Cody Potter - Posted on December 29, 2023

Layered Architecture in Go

Motivation

There is a need to implement consistent architectural language in large Go services. One such pattern that has proven to work well is the Layered Architecture.

When I talk about architecture, I'm not talking about infrastructure. I'm speaking only to code organization for a go project.

This post is a pretty opinionated take on how you could implement this pattern, so take what you like and leave what you don't.

What is a layered architecture?

It's an extremely common and widely used architectural design pattern. It defines an application composed of horizontal layers that function together as one unit of software. We separate the code components logically. Layers may be individual or logical groupings of Go packages.

Closely related patterns include Domain-driven design, N-tiered, Uncle Bob Martin Clean Architecture, Hexagonal, and Ports and Adapters.

Guidelines

Let's start with broad strokes before we dive into the code.

Layered Packages

A layered package is a go package that aligns with the following principles:

- Layered packages must only import their immediate child or any neutral packages. The compiler's import cycle detection will help to enforce this. It's up to you to avoid "skipping a layer" by calling a method from a layer 2 steps down, for example. Following this principle will make testing easier (more on this later). This principle aligns with the Law of Demeter, i.e. "Only talk to your immediate friends".

- Global shared variables are not welcome in layered packages. Eliminating globals means eliminating side effects and hard-to-read code. Minimizing variable scope is a core tenet of clean code. This concept is covered extensively in Code Complete.

- Layer implementations (structs) should have an interface that describes its functionality to the layer above. This interface can be defined in the layer itself or the parent layer. Whatever makes the most intuitive sense to you.

- Layered packages should have a New() function that creates and configures a new instance of the component that satisfies the interface described in principle 3. Principles 3 and 4 correlate to a popular go-ism "accept interfaces, return structs."

- Avoid shared structs that are passed layer to layer. This leads to bloated static data structures that aren't always properly hydrated. Frequently, the field tags will be correct in one layer, but incorrect in another. If you need data transfer objects (DTOs), each layer should have its own DTOs that get returned upward only with the necessary fields. I suggest using arguments/parameters instead of passing DTOs downward. A good rule of thumb is that basic data types get passed down as parameters and structs get returned upward when needed.

Neutral Packages

A neutral package is a go package that isn't part of our layered design. A neutral package can follow its own design rules. A neutral package may not import a layered package nor any neutral packages (Libraries are fine of course). Need to import another neutral package? It’s likely those packages should be joined or refactored into a shared package.

itty bitty social

Let's design a layered architecture for a small social network API. Let's pretend the requirements for this API could grow very rapidly. If we start out with a layered architecture, it will be easy to grow and scale as more requirements are added. For now, we just need to support users and posts using a SQL database and all the http endpoints that go along with the user and post models.

Here's the working example itty-bitty-social

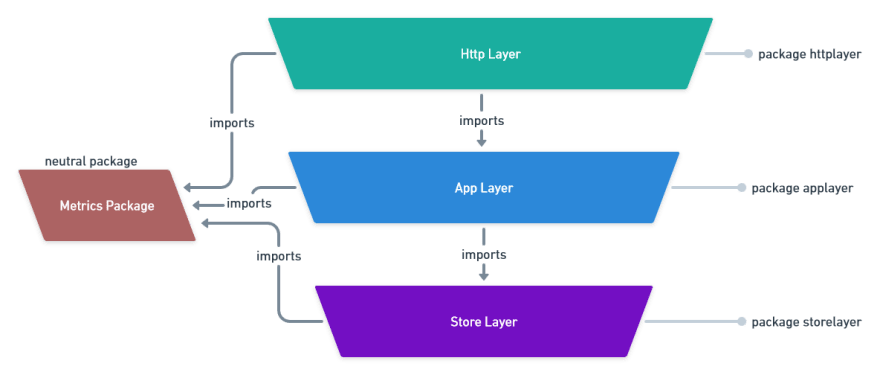

There's a fair amount going on in this diagram, so lets just break it down from the outside in.

There's a fair amount going on in this diagram, so lets just break it down from the outside in.

The layers

- The topmost layer consists of the http API. For simplicity sake, we can call it the http layer. It could also be commonly referred to as the communication or driver layer. This layer could be easily swapped out with a worker pool, a CLI, or a GUI in the future. We'll put our gin router stuff and our authentication logic here.

- Below that is the app layer. Our business logic and authorization will live here. Additionally, we can slice this layer into a collection of interfaces like Post and User and embed them into one App interface if the layer itself becomes too large.

- The third layer is the store layer. We could also call this the repository layer. If we needed to worry about caching in the future, we could split the layer into MySQL and Redis interfaces. We'll put our gorm logic in this layer.

- Finally, the neutral metrics package stands alone. Any layered package can freely import it. We can always add more neutral packages that don't depend on others. Neutral packages must remain neutral, meaning they must strictly not import layered packages nor each other. Else, you risk creating two separate layered architectures in one service (yuck). We don't think of these packages as the final layer, because it would break the rule that layered packages should only import their immediate descendant. For example, the http layer could not import the metrics package if it were the 4th layer.

The code

Setup

Let's walk through a vertical slice of our layers to get an idea of how they are set up.

// main.go

package main

func main() {

// create store layer

storeLayer := storelayer.New()

// create app layer

appLayer := applayer.New(storeLayer)

// create http layer

api := httplayer.New(appLayer)

api.Engage()

}

You can see here how we build the layers from the bottom up, each time using the lower layer to build the layer above. Finally, we engage the http layer.

// httplayer/router.go

package httplayer

import (

...

)

type httpApi struct {

engine *gin.Engine

app applayer.App

}

func New(appLayer applayer.App) *httpApi {

a := &httpApi{

engine: gin.New(),

app: appLayer,

}

a.SetupRoutes()

return a

}

func (self *httpApi) SetupRoutes() {

self.engine.Use(gin.Recovery())

api := self.engine.Group("/api")

{

users := api.Group("/users")

{

users.GET("", self.getAllUsers)

users.POST("", self.createUser)

}

posts := api.Group("/posts")

{

posts.GET("", self.getAllPosts)

posts.POST("", self.createPost)

}

}

}

func (self *httpApi) Engage() {

self.engine.Run()

}

Pardon my use of self as a receiver here. I have a personal dislike of Go's custom receiver names. In my opinion, custom receiver naming is a violation of the go proverb "clear is better than clever". Notice the New function that creates the http api and how it stores the app layer on itself to use later. Also, notice we aren't using any global variables here.

// applayer/app.go

package applayer

import (

...

)

type App interface {

GetAllUsers(ctx context.Context) ([]storelayer.User, error)

CreateUser(ctx context.Context, name, handle string) error

CreatePost(ctx context.Context, content, owner string) error

GetAllPosts(ctx context.Context) ([]Post, error)

}

type app struct {

store storelayer.Store

}

func New(store storelayer.Store) *app {

return &app{

store: store,

}

}

We use the same exact pattern here for the app layer as we did for the http layer.

// storelayer/store.go

package storelayer

import (

)

type Store interface {

CreateUser(ctx context.Context, name, handle string) error

GetAllUsers(ctx context.Context) ([]User, error)

CreatePost(ctx context.Context, content, owner string) error

GetAllPosts(ctx context.Context) ([]Post, error)

}

type store struct {

db *gorm.DB

}

func New() *store {

db, err := gorm.Open(sqlite.Open("itty-bitty-social.db"), &gorm.Config{})

if err != nil {

panic("failed to connect database")

}

db.AutoMigrate(&User{})

db.AutoMigrate(&Post{})

return &store{

db: db,

}

}

Same old song and dance. One interesting thing to note here is how we're storing the reference to the gorm db. It's not a global like you might commonly see. Notice we set up the connection in the New function.

That's how the layers are linked together. Now let's explore a vertical slice of how a request gets fulfilled.

Request Walkthrough

// httplayer/posts.go

package httplayer

...

func (self *httpApi) createPost(c *gin.Context) {

newPost := &post{}

err := c.BindJSON(newPost)

if err != nil {

logrus.Error("failed to bind in create post: %v", err)

c.AbortWithStatusJSON(http.StatusInternalServerError, gin.H{

"message": err.Error(),

})

return

}

// TODO: should set post.owner from auth

err = self.app.CreatePost(c, newPost.Content, "noodle")

if err != nil {

logrus.Error("failed to create post: %v", err)

c.AbortWithStatusJSON(http.StatusInternalServerError, gin.H{

"message": err.Error(),

})

return

}

c.JSON(http.StatusAccepted, gin.H{

"message": "created successfully",

})

}

The above code is part of the http layer, so it only has 3 responsibilities.

- Parse the request

- Call into the application layer

- Decide how to respond

Notice that if the app layer func CreatePost has an err, we will respond with an appropriate http status code and response. We could use a switch here to parse out sentinel errors from the app layer to make better decisions on the response if different issues could occur in the app layer.

// applayer/posts.go

package applayer

...

func (self *app) CreatePost(ctx context.Context, content, owner string) error {

return self.store.CreatePost(ctx, content, owner)

}

For the above example, the app layer is just immediately calling the store layer, because we don’t need to add any business logic here. However, this would be a good place to emit metrics, check if the user is banned from posting, or any other “business rules” you could think of.

You might be tempted to omit this method and instead do something like self.appLayer.storeLayer.CreatePost(...), but this is a violation of the Law of Demeter and creates an interdependency. It's best to avoid this and leave this little wrapper function in place. Here's an awesome article about interdependence to check out if you're curious about the motivation here.

// storelayer/posts.go

package storelayer

...

func (self *store) CreatePost(ctx context.Context, content, owner string) error {

user := &User{}

err := self.db.Limit(1).Find(user, "handle = ?", owner).Error

if err != nil {

return err

}

err = self.db.WithContext(ctx).Create(&Post{

Content: content,

UserID: user.ID,

}).Error

if err != nil {

return err

}

return nil

}

Any errors that occur here will get passed all the way back up to the http layer and emit a 500. To take this a step further, we should return a store layer sentinel error if the user is not found. Then the app layer would check for that sentinel and return an appropriately detailed error to the http layer so we could return a 4**.

Testing

One of the huge benefits to this pattern is testability. Since each layer is injected into each parent layer, we can generate mocks for each layer and inject those instead. For this code we could easily achieve 100% code coverage when unit testing each layer, since we have full control of the child layers. A great tool to use for generating mocks from interfaces is vektra/mokery. One command will create mocks for each of your interfaces that we can inject during test.

In summary

Thanks for reading! I hope this was a helpful example for understanding the layering design pattern. I appreciate any feedback or questions you might have. If you’d like to see a follow up post on writing unit tests in this pattern, I’m happy to write it up.

Going further

As you take this pattern further, you may find that your layers grow too large. Large interfaces weaken abstraction. To work around this, consider either: A. Split your layer into smaller layers. You can always add more layers. B. Split your layer into vertical slices. You can slice a layer's interfaces into smaller interfaces, then the consuming parent can define its own interface for the child, embedding the smaller interfaces into one.